“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.” - Marcel Proust

Whenever we aim to embark on any new journey, we do not rush headlong into the unknown. Sure, the thrill seekers out there may enjoy a series of unpredictable twists and turns, but as far as teaching and learning are concerned, a modicum of planning can go a long way. The question we’re often confronted with is, “Where do I start?”

The right answer through the right question

Research is so much more than just finding information. It can be quite an intense (and sometimes overwhelming), very human activity; it requires us to engage with the learning process on more than just an intellectual level. Even with the most rudimentary of fact-finding missions, it is crucial that we aim our efforts at more than just discovery ‒ we need to determine our line

of questioning and the reason for said questioning in order to structure our research optimally. We need to start by asking ourselves

the right questions.

When determining where to start, our questions should be aimed at qualitative answers, rather than quantitative ones. This can help educators, learners and other role-players prioritise interests, fields of focus, and goals. When determining which goals to prioritise, one should aim at breaking them up into short-term, long-term, and interim goals, all of which can branch out into subsidiary and ancillary steps. This is done in order to place emphasis on long-term success over temporary gain or quantifiable improvements in assessments or learner achievement.

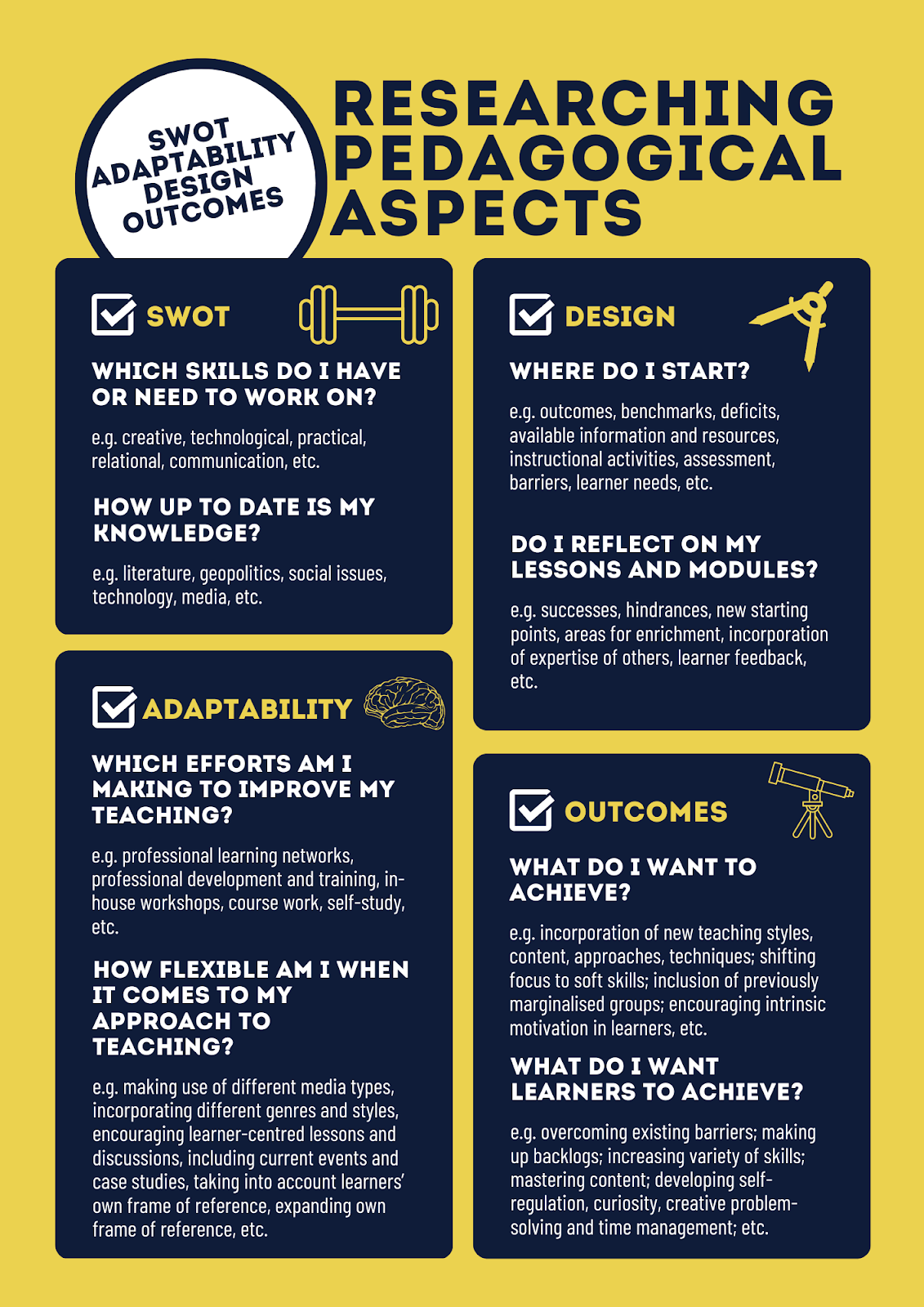

When one has been in the education game for a number of years, one tends to get stuck in a rut, whether subconsciously or intentionally. Though there is comfort to be found in the familiar, the reliable, there is always much to learn through a little introspection, starting with a critical reflection on and evaluation of one’s own teaching. Which aspects of our own pedagogical approaches need to be researched and questioned?

Once available skills & resources have been identified and questions have been aligned to the teaching goal, organisation and structure of those elements become key. Let’s assume the aim in all teaching and learning is quality, in the educator, the content and skills being taught, as well as the learning experience on the whole. Generally speaking, the quality of the teaching and learning experience is determined by the quality of the teacher and that which he or she values. An educator who values professional growth, and is willing to undertake the voyage of discovery regarding their own pedagogical philosophy, will achieve excellence in their school setting and inspire their learners to strive for competence and personal excellence, regardless of abilities and circumstances.

When designing and structuring an approach to teaching, one must align one’s findings in an efficient, effective, and fair way, in order for all stakeholders to benefit. There needs to be a clear link between the identified shortcomings or areas that can be improved, and the points that one plans to implement in order to achieve this. One needs to determine whether one first needs to address areas that are lacking; alternatively, one can decide to focus on that which has already been mastered or comprehended, in order to use that as a solid foundation. Each of these has its merits and it is up to the educator to determine, and re-evaluate where necessary, which areas to attend to first. In this way, we alter and adjust our approach to education in order to accommodate learners and other stakeholders in a multitude of settings and contexts.

To a great extent, the long-term vision of the educator embarking on this journey of discovery determines the way in which success will be measured and to what extent it will be achieved. Not all success is necessarily quantifiable in the traditional way of being able to check a list or obtain a high score. Where research in the RIDE approach is concerned, success is often determined by the quality of the starting point that the process is being undertaken from. The approach is a series of processes that loops back on itself, determining new starting points when new obstacles or challenges are identified.

When researching any given topic or context, one needs to progress from the supposition that something new will be garnered, created or questioned, though the solutions may not necessarily yet be evident. During the research process, we query what we know, gather material, collect data, and otherwise engage with existing facts or the status quo. In essence, it is determining which questions to ask in order to find the most useful and insightful answers. Research is done in order to determine a starting point for our journeys of discovery. When speaking in The Republic, Plato said it best, “The beginning is the most important of the work.”

Pages

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.