I love teaching literature; focusing on the different figures of speech, the expressive ways in which a poet can describe something ordinary and the meaningful discussions I get to have with my children about life. Whenever I prepare for a poetry lesson, I put in extra time to plan strategies that will ensure I captivate the class.

It was while teaching the poem Leather Jackets, Bikes and Birds by Robert Davies that I had an epiphany.

I remember printing pictures to help my class visualise the gangs; we discussed every single figure of speech; and dissected every word (even “snogging” - which caused an eruption of laughter). It was a lively discussion with maximum student engagement. The epitome of a successful lesson.

The following day, I confidently started my Grade 9 English class with, “The poem speaks about the need for acceptance, where the need to belong is so strong that teenagers would go to extreme measures in order to be accepted, loved and acknowledged for who they think they must be.” Passionately I looked at my class, in anticipation of an eruption of rich conversation.

Instead, they stared at me. Blank.

One boy raised his hand. “But Ma’am, they were clearly accepted because they were snogging in the spotlight.”

My heart sank while the teenagers continued to think about snogging.

How did I get it so wrong?

I am assuming teachers across our country can relate to the above-described scenario. Teaching your heart out for an entire period, only to find out later that no knowledge remained.

Down the rabbit hole

That day I started down a rabbit hole to find a solution to my problem: Why, if I prepare and share the lesson in a creative, interactive way, are they not learning?

I found my answer in the research of two writers: Dan Willingham and Anders Ericson.

Willingham explains how learners learn very effectively in his book, Why Don’t Students Like School? Students tend to dislike school because variant stakeholders in education do not fully understand some of the critical cognitive principles involved in learning. Willingham describes two types of memories that are involved in the learning process, namely: long-term and working memory. Some of the best strategies for learning involves pattern recognition and “chunking” information for the long-term memory.

The simple answer, therefore, is that the information that we share with our kids rarely transfers to their long-term memory. It remains in the short-term memory, for a while, and the following day, or in a week’s time the information has disappeared.

The above led to my A-HA moment: We learn what we actively think about.

In that lesson, I was doing all the thinking and the kids were not actively engaged in the process of learning.

We started implementing a technique referred to as the gradual release of information. In our school, it’s also known as the I Do, We Do, You Do. After implementing this method in my own class, my students’ marks increased drastically. What makes this more exciting is that it is a rather simple technique!

When taking a closer look at the concept of a gradual release of information, you will notice that it correlates with how we learn most new things.

Take, for example, teaching someone how to ride a bicycle: First you get on the bike and show them how it looks. Then, you put the child on the saddle, but hold on and walk with them. This builds confidence and gives the child the opportunity to familiarise themselves with the process while feeling safe, with your support. After walking with them for a while, you let go and just like that another cyclist is in the making.

The same applies for learning how to cook. We first watch our parents cook, after a while we might start helping with the small tasks. Years later, we find ourselves in the kitchen cooking family recipes without even looking at a book.

Gradual release of information in the classroom setting follows the same principles.

- The ‘I Do’ phase is led by the teacher. During this phase the teacher will share new knowledge, introduce a new concept, or teach the class how to do something unfamiliar to them. As the learner obtains the new information and skills, the responsibility of learning moves from teacher-directed instruction to student-processing activities.

- In the ‘We Do’ phase of learning, the teacher continues to question, prompt, model and cue learners. The We Do phase allows for a deeper level of learning. Learners are now actively engaged in the content - they are thinking.

- Lastly, the ‘You Do’ phase of the lesson is a complete release of responsibility to the learner, as they work independently - also referred to as independent practice. During this time, the teacher provides additional support, as needed, but student learning is self-directed.

The final part of the lesson is where the magic happens, as Doug Lemov emphasises,

“Independent practice is really where our work as teachers comes to life. It’s the moment when we stop talking and stop doing the work and allow students to test out their own understanding, to make mistakes and to ultimately understand more deeply by learning from those mistakes.”

That brings us to the work of the second writer that changed my understanding of teaching and learning: Anders Ericson.

Anders Ericsson focuses on the concept of “deliberate practice”. This process involves immediate feedback, goals, and a focus on a specific technique. He states that a lack of deliberate practice can be the reason why so many people reach only basic proficiency at something, whether it be a sport, profession, or academics.

In his book, Peak, he argues that the right kind of practice carried out over a sufficient period, leads to improvement. Nothing else. According to him, there is no such thing as natural talent.

“If you teach a student fact, concepts, and rules, those things go into long-term memory as individual pieces, and if a student then wishes to do something with them—use them to solve a problem, reason with them to answer a question, or organise and analyse them to come up with a theme or a hypothesis—the limitations of attention and short-term memory kick in.”

“The student must keep all of these different, unconnected pieces in mind while working with them toward a solution. However, if this information is assimilated as part of building mental representations aimed at doing something, the individual pieces become part of an interconnected pattern that provides context and meaning to the information, making it easier to work with. […] you don’t build mental representations by thinking about something; you build them by trying to do something, failing, revising, and trying again, over and over. When you’re done, not only have you developed an effective mental representation for the skill you were developing, but you have also absorbed a great deal of information connected with that skill.”

As teachers, our purpose is to do just that…teach.

Teaching includes understanding how we learn to be able to choose a method that will optimise the learning experience. Changing the way I teach shifted my focus away from what I am teaching to what my students are learning. And its evidence in their results.

Renate Van Der Westhuizen

Principal

Apex High School

Sometimes, teaching reminds me of the legend of Sisyphus.

In Greek mythology, we learn about Sisyphus, the king of Corinth. He was known for his trickery, but it was his cheating of death that infuriated the gods most. Zeus punished Sisyphus for his death-defying tricks by forcing him to roll an immense boulder up a hill, only - naturally - for it to roll back down every time it neared the top. He was doomed to repeat this action for eternity.

Teaching can sometimes feel the same.

We start at the bottom of the hill, paving the way to the top with meticulously designed lesson plans, supporting resources, and formal assessments of high quality. We put all our effort in, to push that massive boulder of knowledge up the hill.

Along the way, we ensure our learners are still on track, with questions like: “Do you all understand?” and “Are you with me?” In response, we see heads nodding. The top of the hill takes the form of a formal assessment. But once we start marking, the boulder rolls right back down to the bottom. Defeated, we capture disappointing results, and come next term: We start pushing up that boulder again…

“Insanity is doing the same thing, over and over again, but expecting different results.” - Albert Einstein.

Unlike Sisyphus, we are not doomed to repeat the same task for eternity. We can change our course to get that boulder right to the top. It’s called Data Driven Education.

Heather Morlock boldly and accurately stated, "If a child can't learn the way we teach, maybe we should teach the way they learn." But how do I know whether learners are learning the way I teach? Should I wait for June examinations or end-of-the-year finals? The reality is that by the time we are done marking and completing question analyses, it is already too late.

If we only measure whether students have learned what has been taught on a monthly or termly basis, we are solely relying on our opinion or the nodding of heads to predict their success. In a country where quality teaching is desperately needed, it is too risky and too important to make estimated guesses. We need proof; evidence; we need data. We need to be driven by data.

“Data” might seem intimidating and like another “to do” on the already too long list, so what does it entail?

A teacher refers to the CAPS or Annual Teaching Plan to determine what needs to be taught, which becomes the objective of their lesson. Using a data-orientated approach begins during the planning phase: Instead of identifying what will be taught, we should also determine what learners should be able to master by the end of the lesson. Once we have identified that, each skill can be further unpacked to map out a detailed plan.

For example, while teaching a new piece of content in a maths class: To reduce a fraction to its simplest form by canceling.

- During the first lap, the teacher will ensure that their learners can find the highest common factor of both a numerator and a denominator.

- The second lap will be used to monitor that all learners can divide the numerator and denominator by the highest common factor.

- The last lap will monitor that all scholars wrote the answer in its simplest form.

- After teaching the content and identified skills, learners will have time to apply the newly gained knowledge during independent practice, providing the teacher with the ideal opportunity to track responses.

- The teacher circulates with a class list and the teacher exemplar, capturing whether scholars show mastery or not.

- From this, we have evidence; a narrative of where our students are on the hill. We can make a plan for the boulder, we can reroute and thus, there is more than one possible turnoff; more than one push to get them to the top of the hill!

- If a number of learners are making the same error, the teacher can provide batch feedback to the class by briefly interrupting the independent practice and explaining the common error the teacher has noticed and how they can go about fixing the misconception.

- If it is only a few students, individual feedback will be most impactful: It is vital that we do not give our scholars the answer but rather ask guiding questions so that they, themselves, can reach the correct conclusion.

- Should the majority of the class be struggling, the question to ask is, “Where did the misconception come from?” This will determine how a teacher will reteach: Do the learners need to see a model of the thought process? Will guided discourse be more impactful where the class can work through additional examples to deepen their understanding?

If we welcome data into our classrooms, we are far from running out of options and aren’t aimlessly and endlessly pushing the boulder up the hill, fingers crossed that it won’t come tumbling down this time.

For learner results to truly improve, our teaching needs to be responsive. We need to stop rolling the boulder in exactly the same way, day after day. The most effective teachers and leaders know when teaching is working, and when it isn’t, they fix it. Let’s fix it.

Renate Van der Westhuizen

Winner, Excellence in Secondary School Leadership, National Teaching Awards

Principal: Apex High School

“The first prerequisite of being a good teacher is not that you should be good at teaching; the first prerequisite is you must be good at learning.” We can all take a page from the proverbial book of Saif Sarwari; we must indeed be good learners to be good teachers. One of the key aspects of being a good learner is questioning everything… including ourselves and our own (often very set) ways of thinking and executing, of understanding and expressing. We need to ask ourselves what exactly is required when we need to learn and relearn in order to thoroughly evaluate and explain our thought processes. We need to figure out where we can improve and where we are still lacking. Critical reflection on our own teaching and learning is essential. We need to learn to fail, in order to learn to succeed.

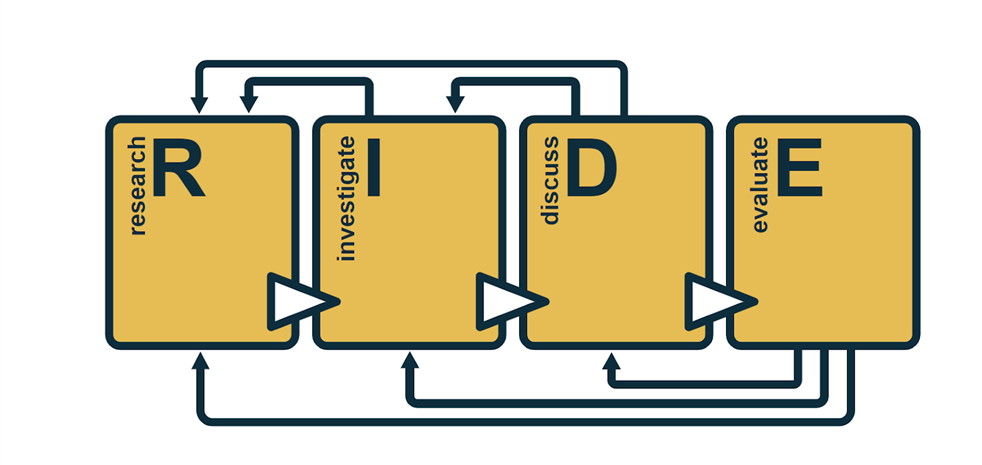

Through the course of the last few years, I have developed an approach to teaching and learning - the RIDE model - that enables teachers to engage with content, processes, tasks, strategies, and overall thinking processes on a much deeper level. It helps us dig a little deeper into our own psyche, our own experiences, and paradigms, encouraging us to truly engage with that which we wish to convey and the way we approach the curriculum, our learners, our colleagues, and overall outcomes.

Every aspect of the RIDE approach (Potgieter, 2021) is aimed at active participation and engagement. Each element is designed to shift back to whichever part of the process is needed to clarify, explain or re-evaluate work. I apply this approach both to my own teaching and when designing tasks for my learners. It makes sense for people like me, who have so many thoughts competing for the same attention, to have a structure, a recipe of sorts, to approach intricate projects where we work with other people. If I can pinpoint where I am in this process, it makes it so much easier to go back and identify where I can improve.

The RIDE model empowers teachers and learners alike to engage so much more critically with content and tasks. My upcoming blog series of posts will focus on deconstructing each section of the RIDE model, explaining how each facet is linked with the rest, and how progression through and engagement with this model can help improve the quality of material, diversity of approaches, the efficacy of tasks, and relevance of assessments. I am a firm believer that the quality of the learning experience that teachers engage in, is directly reflected in the quality of the work they do and the contribution that they are able to make to the holistic development of their learners and peers.

Many of us are comfortable engaging with that which is familiar and comfortable. We have become so used to repeating and regurgitating what we have learned, that there is no room for reflection… no room for failure. We must allow ourselves to delve into our thought processes, the way we structure our work, our tasks, our assessments and our own learning; we need to allow ourselves to fail in order to learn. The RIDE approach offers us a unique opportunity to turn our failures into teachable moments, into opportunities, rather than setbacks. Once we are comfortable with failure, we are in a perfect position to engage with the processes that brought about failure, so that we may improve (or dare I say perfect?) what we do.

This is part one in a blog series about the RIDE approach. I look forward to sharing some more insights into this approach in the coming weeks.

Nikki Potgieter

Teaching is gruelling and arduous. If you are not fighting with the learners, you are fighting the parents for fighting with the learners. In general, there seems to be a decrease in respect for teachers. Overcrowded classrooms are filled with numerous learning gaps and the admin load is tremendous and endless. As if the fighting, explaining, complaining, and teaching is not enough, just before the bell rings to announce the end of break, before you can make coffee or visit the bathroom…the copier jams!

On top of the above oh-so-familiar battles, we had to face and continue to survive a pandemic. One where the everyday man showed us the lack of appreciation for teachers, with questions like, “Why do they need to get paid? They are not even teaching in class right now.” These are the types of comments we must endure, all while pushing to ensure scholars are receiving their basic right to education. Lessons on Google classroom, WhatsApp groups, voice notes, and Facebook pages to mention a few, have integrated into the world of the teacher.

This reminds me of the words of George Bernard Shaw. Words that I have unfortunately heard too many times before: “Those who can do; those who can’t teach.” Sir Shaw got it all wrong back in 1903, if I could have coffee with him, I would have responded, “Those who can, teach to inspire. Those who can’t…won’t survive a day in education.”

We become teachers, because of our passion; a passion to bring change and meaning. Living our passion can be challenging. It leaves us exposed, emotionally involved, and tired. So why keep going? Why not just follow the lead of so many others by merely quitting the sector or our country? I do not think the answer lies in a big revelation, but rather in moments…

Every afternoon I try to stand outside the gate as our scholars dismiss. One day, as Mark leaves, he turns back and asks me if he can show me something. At this stage, Mark is a grade 11 learner, a few years older than the rest of his cohort. You can see that he knows the hardships of life. He has lived. He has suffered. He pulls out a creased piece of paper and tells me that he found it whilst cleaning his cupboard. Unfolding the paper, I was faced with the worst report ever seen. Some subjects have 0% next to it and there is not one mark more than 15%.

Confused, I look at Mark, he tells me that that was his report before he came to our school. That he failed grade 8 and then again in grade 9, after which he dropped out and got involved in gangsterism. When his mom enrolled him in the “new” school in Eerste river, he thought to himself: “different school, same story…”

And then he thanked me. For changing his life. I was blown away. I responded that we are not to be thanked, as he made the choice to take ownership of his future, besides I did not even teach him. Mark then responded with these words, “No Ma’am, but you hire teachers who care”.

Mark matriculated in 2021 with a Bachelor pass and is going to pursue a career in the Tourism industry. We use his story to motivate other learners to take ownership of their own studies.

To be honest, I did not even know that Mark knew his teachers’ names. But he did and they impacted his life in such a way that he wanted to spread the message to everyone who would listen. Their passion ignited his passion. They taught to inspire, and it changed Mark forever.

There are thousands of “Marks” in our system, young children with no role models. Young children who failed and who are ready to give up. We cannot give up on them. It is just simply too important. We may get tired, dismayed, and have moments of hopelessness, but then we need to remember why we wanted to be teachers in the first place. Was it to provide opportunities you did not have, to protect, inform or empower? Even though the classroom has changed, chances are you will find your reasons just as relevant as day one of your teaching career.

The responsibility lies with us to not forget why we chose the road less paved and organized. It is like Josh Shipp once said, “Every kid is one caring adult away from being a success story.”

In conclusion, if you are a teacher and reading this: thank you! Thank you for doing the most important job. A school is because of its teachers. A country is because of its teachers.

Renate Van der Westhuizen

Winner, Excellence in Secondary School Leadership, National Teaching Awards

Principal: Apex High School

Photo 1 by Advanced Digital Copiers

Photo 2 by Kenny Eliason on Unsplash

Everyone has seen the thunder god Thor wield his mighty hammer, Mjöllnir, as a symbol of his power, but there is a catch… Only the worthy will be able to lift this magnificent tool, forged in the heart of a dying star. Regardless of how strong other gods and mortals may think they are, they are usually unable to wield this impressive weapon. Because Thor is better known for brawn than brains, he often resorts to swinging his trusty mallet every which way when trying to solve a problem. The problem is, that when all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. Abraham Maslow most certainly hit the nail on the head when he proposed the concept commonly referred to as the “law of the instrument”. It refers to the over-reliance or dependence on a favourite or familiar tool.

Consider your favourite ICT tool. This is your hammer. Oftentimes, people are overwhelmed by the number of tools available and will simply give up before taking on a new or challenging project. This is where innovation is smothered before it even has a chance to shine, burn, and ignite a series of thoughts and actions that may have transformed the way the problem could have been solved. We need to ask ourselves what we have at our disposal and evaluate the possible applications of whichever tool is available. Something as basic as word processing tools can be used to encourage collaboration, gather and evaluate data and elevate the presentation of one’s findings. If that’s your hammer, challenge yourself to either diversify the applications of that tool or become an innovator that applies that tool in a previously unseen manner.

The Latin innovatus refers to introducing something new. Even a seemingly simple tool can always be improved upon, refined, amplified, specialised or utilised in an alternative way. We need to evaluate which aspects of the familiar tools at our disposal are most useful and which could possibly be completed more efficiently or easily with an alternative approach or tool. What we are essentially doing, is evaluating our own thought processes in order to ascertain where we can improve our skills or the use of an existing tool. To a certain extent, it takes the pressure off the one who wields the hammer – find renewal in that with which you are comfortable. This gives us the courage to explore new tools when we have exhausted the applications of that on which we have come to rely.

People are usually hesitant to commit to the unfamiliar. The cautious among us do not rush headlong into new fads but prefer to observe from afar, eventually deciding whether a new idea is worth the hype that surrounds it. An alternative to jumping on every new bandwagon that comes along is to consult those already in the know. When we are open to learning from others (or the mistakes of others), the approaches and skills we are exposed to can exponentially multiply our capacity for problem-solving. Because we are creatures of habit, seeing someone else successfully utilise a new or unfamiliar tool, could be just the push that we need to leave our comfort zone… a carpenter's shop filled with hammers. There is great value in shared and collective knowledge. We must strive to surround ourselves with people from whom we can learn, and who can learn from us. Borrowing from the toolbox of another is a way in which we can diversify our skills and approaches.

With so many new tools being added to our colleagues’ workshops and toolboxes each year, it is so tempting to replace our trusty hammers with something bigger, but we must resist. We need to gradually build on what we know, improve and hone our skills, in order to teach the novice woodworkers the basics. We don’t get rid of what works; we use it as a starting point for innovation.

Even the most skilled and experienced carpenter has a hammer (or an entire range of specialised hammers) in their workshop. We are often afraid of letting go of the familiar or feel forced to change and renew, all at the cost of what we have already learned and acquired. The aim of renewal is not to replace that which works well, but to improve upon it, to optimise it. Only once we master a new tool, do we feel comfortable enough to venture into the unknown, acquiring new tools and skills.

The word “reinvention” always seems like a misnomer to me. The invention in the strictest sense of the word comes down to creating something completely new, something heretofore unseen, something never experienced or even fathomed. This is not the case when it comes to the proverbial hammer in question. Innovation, on the other hand, takes that which has been, and alters it, improves upon it, optimises it so that it functions in a new way or fulfills a new purpose, or plays a role in a new approach to an old problem. This is up to those of us playing at Thor. We are worthy… of the role of innovators.

Nikki Potgieter

La Rochelle Primary School for Girls

2nd Runner Up, National Teaching Awards 2021 in the Technology-Enhanced Teaching and Learning Category

Pages

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.