Alice Wellington Rollins said that the test of a good teacher is not how many questions he can ask his pupils that they will answer readily, but how many questions he inspires them to ask him - which he finds hard to answer.

Easier said than done.

It seems nowadays to just get a learner to greet you in class is an unsurmountable task in itself. I suppose one of the reasons for that could be the years and years of fostering a fixed mindset instead of a growth mindset.

I believe the answer to Alice Rollins's challenge is first to create a positive classroom culture and then promote a growth mindset. But promoting a growth mindset in our classrooms is not as easy as flipping a switch and then, suddenly, we have a class in which all our learners are eager to learn, love challenges, and make multiple mistakes without giving up. It takes meticulous planning and purposefully changing the words we use.

The key ingredient to fostering a growth mindset

I certainly do not have all the answers, but this is how we created a growth mindset culture in our school. We learned early on that even the best teaching techniques and methods will fall flat if the culture in your classroom is not positive.

One of the first aspects of creating a positive classroom environment is trust. Learners have to believe that you want the best for them, and they will try their best as a result.

How to ensure a sense of belonging and trust in your classroom

Before I get to fostering a growth mindset, I want to share a few techniques we use to make learners feel they belong and in doing so create a positive culture. These techniques are all listed in Doug Lemov’s book, ‘Teach like a champion’.

Positive Framing

People are far more motivated by the positive than the negative. Wanting to be successful and seeking praise will spur stronger action than trying to avoid punishment.

Positive Framing is the technique of framing interactions, especially academic or behavioural redirections. Using this technique allows you to give all types of feedback and guidance that can include praise as well as critical or corrective feedback.

Assume the Best

You will agree that as teachers, especially teaching High School learners, we tend to attribute learners’ actions to their character or personality rather than the situation.

At times, we assume intentionality behind a mistake. We can often hear this echoed in our classes. “How many times have I explained this concept?” Or “You would be able to do it if you listened the first time.” When we make comments like this we attribute ill-intention to what could possibly be the result of distraction, lack of practice or honest misunderstanding.

This technique also helps teachers maintain our emotional constancy and stability. One of the most useful words we must remember when using this technique is the word “forget.”

Practical example: “Just a minute; a few of us seem to have forgotten that we are working quietly on our own. Let’s try that again, this time without speaking.

Precise Praise

Where positive framing focuses on how you can make critical feedback feel motivating and caring, precise praise is more about managing positive feedback to maximise its focus and benefit.

Practical example: The learners are busy with independent practise. You want them to use conjunctions to join two sentences, but most learners are using short sentences. The teacher then says: “Well done, Sarah, I love how you use conjunctions to join two sentences.”

Warm and demanding

The magic of this technique lies in the relationship between being the person who can say, “I believe in you and I care about you” and “therefore I will not accept anything but your very best.”

It is when we learn how to be caring, funny, warm, concerned, and nurturing—but at the same time strict, by the book, relentless, and sometimes uncompromising with students. It means establishing the importance of deadlines, expectations and rules, but not because you are their superior, but because you care about them

Emotional Constancy

I think this technique is the most difficult to truly master because as teachers we are human beings with our own troubles and emotions. And when a learner constantly pushes buttons, it can be difficult to control your own emotions.

However, teachers who show this characteristic know that they are the leaders of their classroom and that learners need to be able to experience emotional safety as they figure out how to manage their behaviours and emotions on their own.

A teacher who practices emotional constancy always keeps learning; moving forward with their actions and mindset. Your goal with regard to discipline should be this: “Discipline without emotion.”

The Joy Factor

The J-Factor is a way to integrate joy into the children's learning. Our learners will work harder if they are having fun learning. Creating joy in the classroom in a “punctuated” manner will create a positive classroom environment.

By using this technique, teachers assign work with a substantial amount of enthusiasm, passion, and energy - not to undermine hard work, but to inspire hard work.

Nurturing a growth mindset

Now that we have created a positive classroom, marked with high expectations, trust and joy we are ready to look at a few techniques to create a growth mindset.

- Normalise the struggle. As we have already discussed, when we struggle we build grit and perseverance. Be vocal about this, even model it in your class.

- Embrace the word “yet.” If one of your learners tells you they cannot solve a maths problem, rephrase and say it back to them, “You cannot do the problem yet.”

- Demonstrate errors and celebrate corrections. Mistakes should always be viewed as learning experiences. Teachers can model this technique in reactions to their own mistakes and the steps they make to correct it.

- Set goals. Have you learners set incremental, achievable goals to demonstrate the attainability of growth.

- Encourage engagement with challenges. Depict challenges as fun and exciting - and easy tasks as boring.

- Promote the value of hard tasks to the brain. Emphasise the idea that our brains are flexible “muscles” that can be developed. Too many learners in our classes truly believe that they are not able to do something. Show them the research and the science.

- Implement cooperative learning. Working together to solve problems highlights process and reinforces the importance of getting help and finding solutions. It also deemphasises individual outcomes.

- Provide challenges. A massive part of developing a growth mindset is teaching learners to overcome obstacles. A hard math problem or difficult writing assignment that stretches their capabilities can provide opportunities for growth and further instruction that emphasises problem-solving.

- Avoid praising intelligence. When we praise our learners for being smart, we reinforce the idea that intelligence is a fixed trait. Your learners will then have one of two thoughts. “I am smart, I do not have to try harder” or “I am not smart so I do not have to try.”

- Don’t oversimplify. “You can do anything!” could feel like innocent encouragement, but if learners aren’t put in a position to overcome challenges, they will conclude that such declarations are empty, and the teacher will lose credibility.

Being a teacher is a massive responsibility. Perhaps this is a good time to remember a quote by Margaret Sangster, “No one should teach who is not in love with teaching.”

Reference:

1. Chicago. Lemov, Doug. 2014. Teach like a Champion 2.0. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Photo by John Schnobrich on Unsplash

Photo by Santi Vedrí on Unsplash

For years, educators and parents believed that praising children for being smart would increase their self-confidence and help them enjoy learning. We know now this is not true.

“Praising students’ intelligence gives them a short burst of pride,” says Dweck, “followed by a long string of negative consequences.”

This kind of praise forces the child into the innate-intelligence mindset, which makes them more fearful of messing up, less willing to work hard to learn new skills, less adventurous with difficult challenges, more prone to cheat or give up, and less confident in their ability to be successful.

“Praising students for their intelligence, then, hands them not motivation and resilience but a fixed mindset with all its vulnerability,” concludes Dweck.

When we praise students for the processes they use – engagement, perseverance, strategies, improvement – it increases motivation and effort, willingness to try new challenges, greater self-confidence, and a higher level of success.

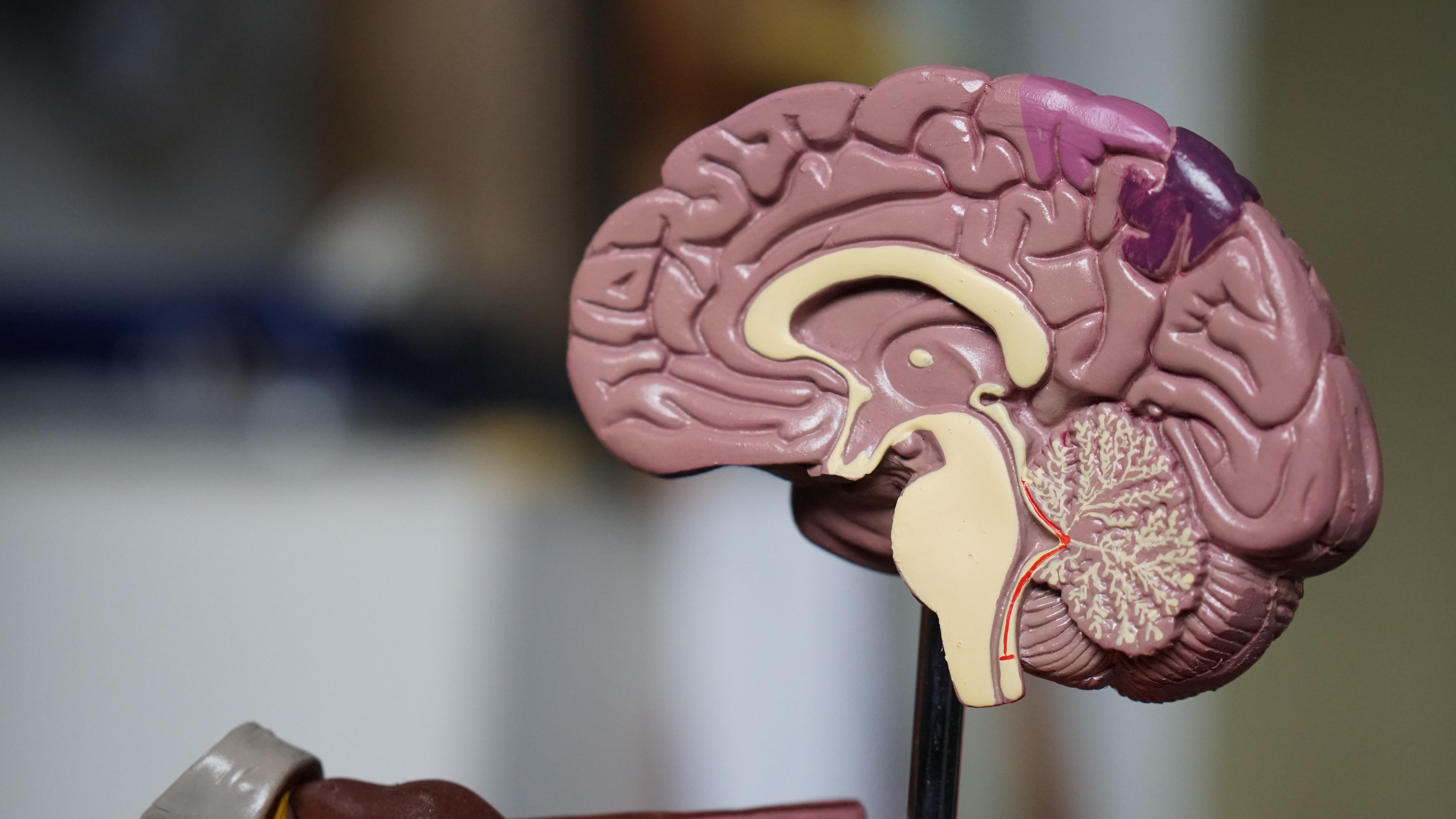

The second driver of our fears comes from within and is referred to as our “lizard brain,” or the Amygdala if you want to be scientific.

The Lizard brain can be located near your brain stem and can also be found in wild animals. The lizard brain is wired to seek safety and help us survive. This is useful when our life is in danger, but when it comes to learning, our lizard brain holds us back.

We have this “lizard” in our brains that basically wants to stop us from making mistakes. The best way not to make a mistake is to not try at all. The lizard brain is the voice in your head that tells you that you are not ready and that you must play it safe. It is why most people hate to speak up or why we dislike asking for help.

Now, imagine you are in grade 8 for the first time. You were brilliant at Maths in Grade 3, but in the intermediate phase, you started struggling. You barely passed Maths in Grade 7, now you are in a class where the top students are getting all the praise for being so brilliant. The lizard brain kicks in and tells you to rather do something that you’re good at. Be funny! Be the clown! And we all know the narrative from there...

The problem is that we cannot kill the lizard brain, or even silence it, but we can learn how to tame it and ride with it. When a feeling of fear or uncertainty arises, it is about taking a breath and asking: Will I be a lizard or a learner?

During the next blog, I will dig into how we can implement the growth mindset into our classes.

Blog Written by:

Renate Van der Westhuizen

Photo 1: Photo by Ismail Salad Osman Hajji dirir on Unsplash

Photo 2: Photo by Robina Weermeijer on Unsplash

That is the question Angela Duckworth asked when she started studying adults in challenging settings. Her research team went to Westpoint Military Academy to predict which cadets would stay and complete their military training.

They also went to a national spelling competition to predict which of the learners would advance the farthest and partnered with a private company to determine which of the salespeople would be the most successful.

In all of their studies, one characteristic emerged as the most significant predictor of success. It wasn’t IQ, their background or physical strength…it was GRIT.

Duckworth defines grit as passion as perseverance for very long-term goals and sticking with your future, day in and day out. Not just for a week or month but for years – until your future becomes reality.

This characteristic is needed for our students

It is clear to see; that this characteristic is exactly what is needed for our learners to excel in school. And the best way to build grit is by… applying a growth mindset.

The idea of a growth mindset was first coined by Carol Dweck at Stanford University and it is the belief that the ability to learn is not fixed; it can change with effort. This is also one of the cornerstones that we build our school on but I will share more about that journey in the next blog.

If a growth mindset is really that simple, the next question must be: Why doesn’t everyone have it? A growth mindset has to do with how we learn and unfortunately, there are some misconceptions about learning.

I am sure you have learned how to do something: Riding a bicycle? Swimming? Juggling? While you were learning, you probably made a lot of mistakes on the way to mastering that skill. The reality is, when we are learning a new skill, it is crucial to make mistakes.

As a child, our mistakes are celebrated. When you learn how to walk and you fall down, everybody cheers for you and they encourage you to try again. They are proud of the fact that you tried and failed.

Unfortunately, somehow this changes as we grow older. A shift happens from celebrating the mistake to punishing mistakes, feeling ashamed of them, and then just avoiding situations where we could possibly make a mistake. One of the reasons why adults are pertinent to learn less than children is because the older you get, the less you are willing to risk.

I am sure you wonder where this fear of failure comes from. Firstly, the fear is fuelled by an external force called feedback. In a study, Carol Dweck discovered some fascinating insights about feedback. They gave hundreds of students an easy test and after the test, half of the students were praised for their ability with feedback such as: “Wow, you must be really smart.” The other half were praised for their effort, with feedback such as “Wow, you must have worked really hard to achieve this.”

After this feedback, an interesting thing started to happen.

First, they gave the students a choice for their next test. They could either take a harder version of the test or they can take another easy version. 67% of the group that was praised for their ability chose to complete the easier test, while 92% of the group that were praised for their effort, chose to complete the difficult test.

Next, they gave all the students a hard test. During this test, Dweck noticed that the group that were praised for their ability quickly became frustrated and gave up early, while the effort group enjoyed the challenge and work harder for longer. There were even differences between the two groups in ethical behaviour. Of the students who were praised for their fixed abilities, 38% inflated their test scores when they reported them, but among those who were praised for effort, only 13% inflated their scores.

Read the next blog as we discuss the impact of praising effort vs ability…

Written by

Renate Van Der WEsthuizen

Pages

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.